As global carbon emissions hit a record 37.4 billion tonnes in 2024, universities are stepping up to meet the climate challenge. Among them, Exeter University has committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2030. But with just five years to go, is this goal achievable?

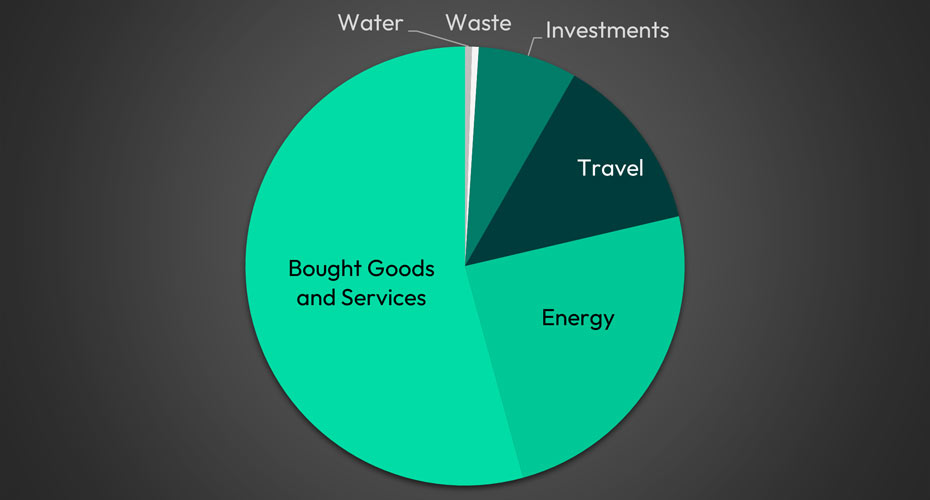

Exeter’s sustainability strategy is part of the broader Net Zero Exeter 2030 Plan, a city-wide initiative aimed at drastically reducing emissions through collaboration between local organisations, including the university. Yet, Exeter faces significant challenges. The university’s biggest hurdle is its Scope 3 emissions, which make up 93% of its carbon footprint. These emissions arise from activities like business travel, student commuting, and the purchase of goods and services, areas that Exeter has limited control over. For instance, 12% of the university’s emissions come from business travel, underscoring the need for a shift toward virtual meetings and sustainable transport options.

However, business travel is just one part of the picture. The largest contributor to Exeter’s emissions is its procurement practices, with bought goods and services accounting for 60% of the university’s total carbon footprint. Addressing this will require engaging suppliers to reduce their environmental impact, an effort that will likely take time to yield significant results. While waste emissions make up only 0.1% of the university’s footprint, Exeter is also focusing on waste reduction and a circular economy approach to minimise resource consumption.

Financial constraints pose another challenge to Exeter’s sustainability ambitions. Reduced government funding has left the university facing a budget gap in implementing the necessary infrastructure changes to meet its low-carbon targets. These challenges are compounded by the university’s reliance on international students and travellers to generate revenue. International students are crucial for Exeter, both financially and in promoting the university’s global profile. The university’s recruitment strategies are built around attracting students from around the world, and the demand for international travel, whether for campus visits or academic conferences, fuels this model. The question remains: will universities like Exeter prioritise sustainability over financial gains when it comes to this reliance on international students and air travel?

While Exeter’s commitment to net zero is laudable, universities are increasingly being forced to balance sustainability with the realities of running a business. Higher education institutions depend on tuition fees, international partnerships, and research funding to stay afloat. Cutting down on air travel or limiting international student numbers could risk their revenue streams. Does Exeter, then, truly have the will to sacrifice short-term financial interests for long-term sustainability? Or are such ambitious climate goals simply a form of greenwashing, aimed at improving public perception without real structural change?

Exeter’s ability to influence local policy, especially in areas like transportation, is also limited. Transportation is primarily managed by local authorities, which restricts the university’s direct control over such emissions-heavy areas. While Exeter can advocate for sustainable policies, these limitations make it difficult to enact broad-reaching changes on its own.

A major concern, however, is transparency. While the university has outlined ambitious goals, there is limited visibility into how progress will be tracked. Without clear metrics and regular updates on emissions reductions, the university risks losing the support of students and staff, who need to see concrete results to maintain trust in the university’s climate commitments. With more than 1,500 climate scientists and environmental researchers on campus, students can play an active role in driving change through research, student-led sustainability projects, and advocacy. Empowering students to track emissions data and push for greater transparency will help foster a deeper sense of ownership and collective responsibility.

Interestingly, Exeter’s net-zero targets contrast with that of its partner, Falmouth University, which has set a more gradual timeline: net-zero by 2040, with 50% emissions reduction by 2025 and 75% by 2030. Falmouth’s slower approach might provide useful insights for Exeter as they work together on shared challenges, such as energy use and transportation.

The question remains: will universities, including Exeter, truly prioritise sustainability over financial needs? If universities depend on international students and air travel, will these sustainability efforts be enough to drive real change?

Exeter’s efforts could be a model for universities worldwide, showing that even in the face of significant challenges, higher education institutions can lead climate action. The question is not whether Exeter can meet its 2030 target, but whether sustainability can coexist with the business of higher education.